We’re not Baskin-Robbins’ flavors

or

The commodification of immigrant women in the age of Trump

I remember throwing my hat in the NYC dating ring over the course of my twenties and watching the energy shift when topics of conversation included my place of origin. I was born in the Southern hemisphere in what is infamously considered a joyfully rhythmic, occasionally dangerous, and very sexy country. In three shakes of lamb’s tail and from context clues alone I bet you, dear reader, have already narrowed down your top choices of where in the world that might be. We invented samba. Enough said.

Skirting stereotypes about what I may or may not like to do in my private life based on the longitude and latitude of my birth is loaded. Bodies clothed scantily in the equatorial heat are both mundane and celebrated in the city of my birth. They are everywhere and not always beautiful. They are background noise in Copacabana, they are moving, selling agua de coco on the beach, and hawking newspapers with the local futebol scores from a corner stand on crumbling Portuguese tiles. Yet, traditional beauty is still a frequent topic of conversation, I internalized early on it was one of my many responsibilities as a dutiful Latinx daughter to uphold. Growing up we didn’t talk about the patriarchy, but in casual conversation my granny (my vovó) told me once in Portuguese I should feel lucky I didn’t need a boob job.

My ethnicity was a double edged sword. In NYC I celebrated, albeit guiltily, how easily I could re-direct a struggling first-date conversation by translating a few bossa nova lyrics into English. I’d point out to my potential suitors in occasionally annoyed flirtation that the original lyrics to Garota de Ipenema (Girl from Ipenema) emphasize grace, not the somewhat banal English re-imagination of being tall and tan. Yet, I stood on the shoulders of this same banality, of a plastic surgery industry that named a procedure after a nation’s posterior, and Ivy League educated but un-cultured white boys who saw badly-lit porn films advertising those same posteriors wondered aloud over jack and coke what I’d be like in bed. My avó will thank São Jorge (Saint George) to know, they were not allowed in my bed.

I tried to explain, in my own broken perspective as an Americanized mixed-cultured Brazilian woman, that they were missing the point. I tried to explain about the actual poetry and playful word play in bossa nova lyrics, and about magical realism, and the pointed satire of Brazil’s own Shakespeare—the mixed-raced Machado de Assis. I would smile and quote Paulo Coelho and all the while wonder what I was doing here. I grew up creative, smart, and painfully shy, and being the fiery, adventurous, and beautiful Brazilian woman with a capitol “B” felt like donning an over-rehearsed part in a long-running sitcom. It was easy to play but it was also only fun for about five minutes.

Most people in Brazil do not look like supermodels—we come in a countless different shades and body types. Despite the hijacking of the lyrics of Vincius de Moraes’ famous song, very few are tall, though many are tan. At 5’10” I am frequently gaped at and called a gringa in Rio de Janeiro.

There is a culture of both grace and oppression, protest and poverty. Brazilian jazz is organic and earthy but absurdly difficult to reproduce. Many things are like this in Brazil. The religion, a mixture of toned-down Catholicism with a dose of ancestor communion and the invocation of the Yoruba pantheon. The myth of the Brazilian woman is all marketing, a highly twisted and filtered aspect of a rich and complicated culture.

That’s what it’s like to be an immigrant woman who is also not an immigrant. That’s what it’s like to lead with your exoticism because you know that’s what’s expected of you, and for me, it damn near drove me mad.

My own identity is complicated and multi-hyphenated. Frequently, when someone innocuously asks me where I grew up, I insert a pregnant pause and laugh before launching into a perfect storm of unlikely middle-class globetrotting. I am of many places but belong to none of them.

So much of partnering up as a straight ciswoman in a city like New York is sifting through the hordes that treat you like a commodity. It’s about sniffing out the phonies like blood hounds and unceremoniously leaving them behind for São Jorge to skewer churrasco (Brazilian BBQ) style in his pit of dragons. Being an immigrant woman (a box I myself don’t even neatly fit into) makes things much more nuanced. There are power plays that go down, a fetishization by American men that is experienced by woman born in second- and third-world countries that runs deep in the psyche of the United States. I can’t help but viscerally shudder every time the President obtusely strides ahead of his Slovenian-born wife at public functions or attempts to pull her hips too close during the Inaugural Ball. To me, it feels personal. It hurts.

The very American Lin-Manuel Miranda writes, “immigrants get the job done” in his Hamilton mix-tape, and that work ethic was imprinted on my DNA as soon as I could read and write. Growing up outside of Brazil, I knew as I butted heads with my father over the state of his English conjugation that tacit parental approval was given out only for straight A’s, and that my survival as an adult would be ensured not only with bone-tiring work, but with mastering a veneer of docile domesticity. There is a saying in Portuguese I heard many times growing up that roughly translates to, “you can cook, now you can get married.” To me this meant we expect you to cure cancer, but for God’s sake wear lipstick and cook a nice flan.

The commodification of immigrant women, lit up like the Las Vegas strip by the First Family, has been going on a long time. Enter Eastern European mail order bride sites, the fact that the term “Yellow Fever” is now imbedded into our lexicon to describe the fetishization of East Asian woman, and why in my heart of hearts I believe I was once told this:

My college boyfriend came from a well-off family in the San Franciscan suburbs, and for several years professed his love for me in earnest ways. When we broke up rather unceremoniously it was because he explained without blinking an eyelash he had just met “an Asian nymphomaniac” and he hadn’t “slept with a Black girl yet.” Deadpan I responded, “We’re not Baskin-Robbins’ flavors.”

In the years that followed, I learned that the basic ones expected me to play domestic in public and wild in private. I was a box to check and a commodity they wanted to buy, so as I grew savvier to the motivations of others I learned to toss those unworthy men, too, to São Jorge’s dragons.

What makes the commodification of both immigrant women and people of color particularly dangerous in the Age of Trump, is that, as my over-privileged ex-boyfriend proved a decade ago, this unabashed brand of misogyny has been around for a long time, but now it’s publically sanctioned.

The thing I could not name for so long is what is particularly insidious. There is a complete unawareness, a total lack of shame, and matter of course that comes along with privilege and traditional models of power. The wealthy Baskin-Robbbins boyfriend took things because he wanted them and thought he deserved whatever he wanted. This is not unique when you don’t see others as full people, when women are a means to an end—it breeds violence, manipulation, and coarseness. There was a social contract I encountered again and again, that because I am a woman, that because I had limited financial means, that because I am not a native born American I should know my place and hold my tongue. I should consider myself lucky to be treated badly by the Trumps in communities all over these great United States.

The problem is bigger than I can untangle in 1500 words, and I wonder if that same liberal ex-boyfriend is now holding “Woke” signs at protest marches and never catching the irony of his past actions. I wonder about women like me who straddle multiculturalism and have misogyny coming at them in two languages. Mostly, I hope we can look at others who may be vulnerable and see that having agency in one’s life is a fundamental right. The pursuit of happiness is literally outlined in the constitution, and it does not come at the expense of disenfranchising others. “Don’t tread on me” is a battle cry straight out of the American Revolution, I hold it dearly in my multicultural heart, but wish it was annotated to say, “also, don’t tread on others.”

"Mais Amor Por Favor"/More Love please

The author Jacqui Rego at the Escadaria Selarón in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

photo courtesy of author.

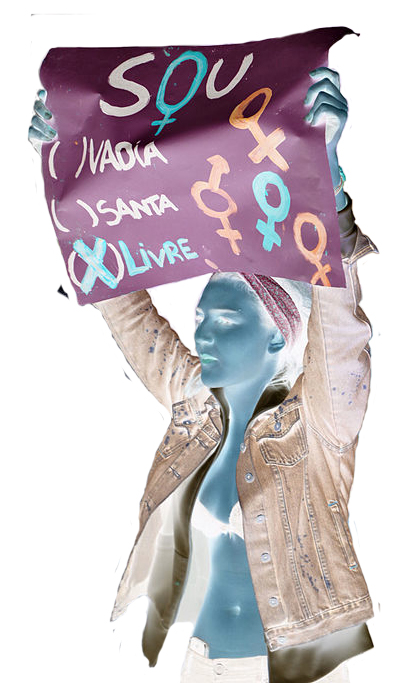

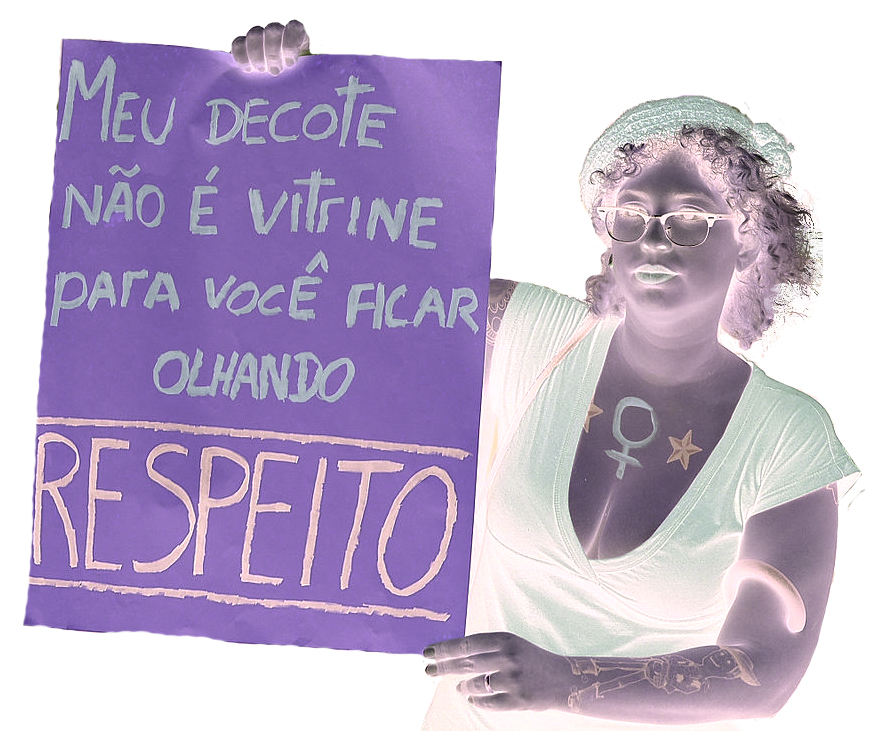

Banner photo:

Denys Argyriou, a Brazilian photographer

Insert photos: edited from creative commons photos of protestors at Slut Walk São Paulo