American Mirage

At first, I thought I knew a lot of things about America.

I had found an old National Geographic in my father’s studio and asked if I could take it home, hiding it in my bedroom so that my little sister wouldn’t ruin it. Flipping through the saturated photos of swimming pools, palm trees, and tan, long legged women in bikinis filled my mind with stars and stripes.

I learned about cherry pie, cowboy boots, and that, unlike in Tel Aviv, it sometimes rained in the summer.

I grew up idolizing Pocahontas and The Little Mermaid. I watched the movies in English, following along with the Hebrew subtitles.

I have only one singular memory of the night we left. At the airport, silently gliding up the escalator, watching the small hunched figure of my grandmother slowly disappear below me. Her little feet in their sensible brown shoes were the last things I saw. I was too young then to realize the immense metaphysical hole I was creating, a vast and nebulous gaping between my present self and all of my past, stretching wildly into our long gone generations upon long gone generations.

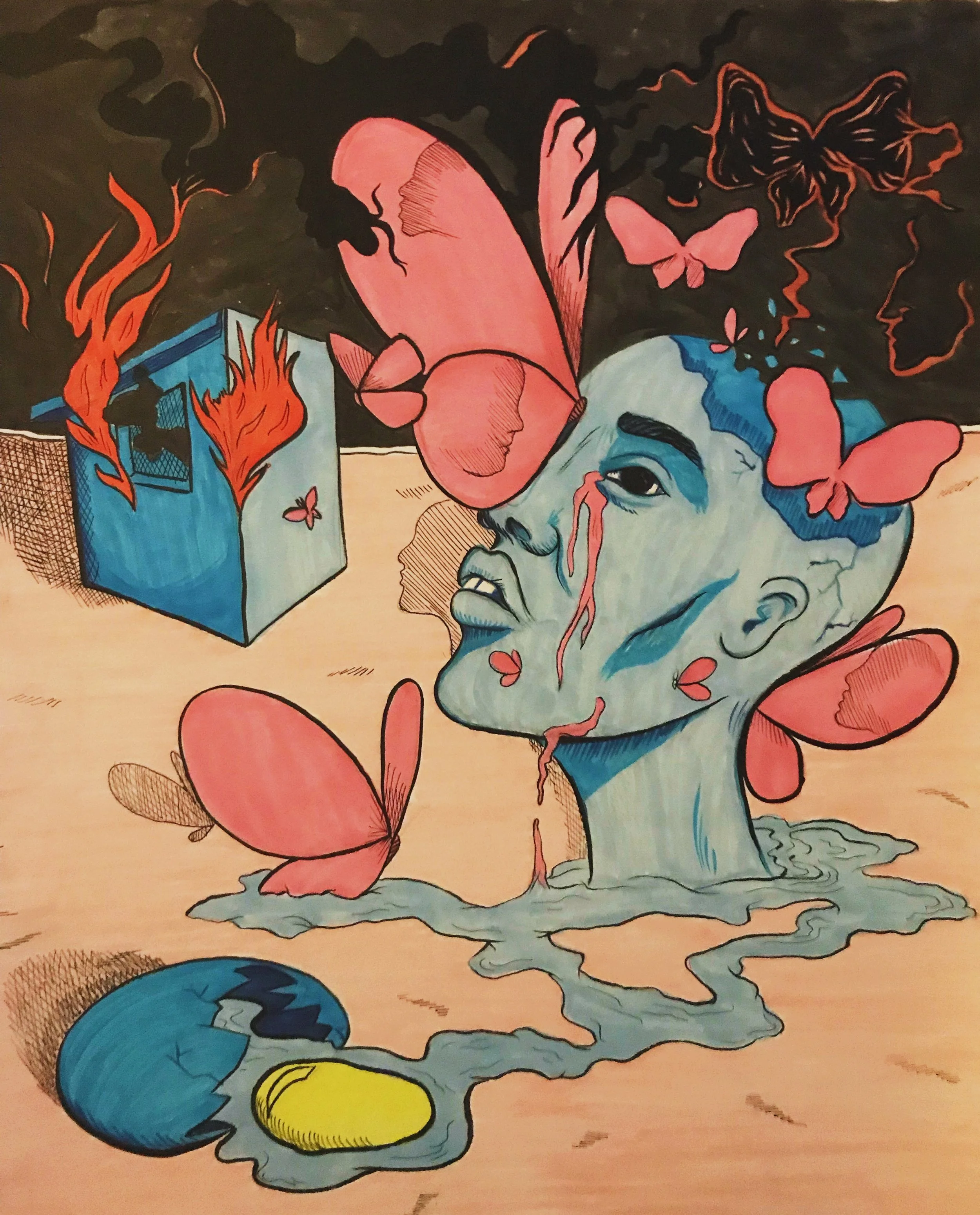

I think from that point on, my soul was split into many different colours, each with its own home, its own root, and they all spread out and ran fast and far away from me, like a scattered rainbow, to try and find out where they truly belonged.

It’s only now, as an adult, that I can begin to reconcile how much I’ve lost, and how much I’ve gained.

The mythology of the U.S., its stoic cultural cannon, soothes me so. Summer camps, canoes, sprinklers watering lush lawns at dusk. The smell of a propane barbecue, the fresh rubber stench of a can of tennis balls, full fat sour cream, half and half. The dream of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Larry McMurtry, all spread out and with a thousand green miles between them; a million different stories hiding in that distance. That history makes me feel safe, it makes me feel rich even when I’m penniless.

America offered me and my family physical safety in a world where there had previously been none. It gave us privacy that at first felt alienating. Not being physically close to my neighbors, being able to occupy a lot of space, felt eerie and lonely, but it also felt immensely luxurious and unbelievably frivolous. Everybody smiled, even strangers. People didn’t smoke inside or yell at each other in traffic.

I’ve tried lots of different ways to be American, hoping to catch the right wind, like an effortless hawk riding thermals. I hung out with cheerleaders and ate cheeseburgers. I shaved my head and listened to The Talking Heads. I grew all my hair back and went to ride horses in Wyoming. I had breakfast at Tiffany’s in New York City and my newest American adventure is working in Hollywood and living in Los Angeles.

These days I feel so much more at peace with my homeless soul. My parents’ accents are endearing instead of embarrassing. Our strange food at Thanksgiving feels delicious and decadent instead of weird and othering.

There’s so much I want to say about being an immigrant, so much I want to share with you about the sadness and the joy, the mixed feelings of superiority and inferiority that come with this experience. But there is no amount of telling, of writing and re-writing, that will make you feel how I’ve felt, or give you the perfect image that I am intending.

I feel so American, but also so not. I heard another immigrant describe his experience and nothing has ever felt more accurate. He spoke about how having his feet in two worlds sometimes brings about a great imbalance, the constant discomfort, the fear of toppling over from the lack of support.

But a foot on either side of a great chasm is also something much more familiar, something much stronger. It is a bridge, and a bridge stands alone on either side. A bridge carries messages and memories from one place to another and then back again, a bridge on the horizon instills an industrious hope in everyone that sees it.

Most importantly of all, and perhaps the most comforting thing about a bridge is that…

It lives in two places at once!

The photos illustrating this essay were both taken by Flip Schulke circa 1975 in New Ulm, Minnesota and are courtesy of the US National Archives. New Ulm is a town of 13,000 in a farming area of south central Minnesota. It was founded by a German immigrant Land Company in 1854 that encouraged its kinsmen to emigrate from Europe to the town founded on ideals of community, freethinking, and harmony with nature.