Murder in Matera

Introduction by Christina Roman

She grew up hearing the stories of her great-great- grandmother: Vita was vivacious, with perfect skin, and left Italy with blood on her hands. Helene Stapinski’s newest book, Murder In Matera, is a richly researched dive to discover the truth about the mysterious murder in her family history. And unlike her previous book, Five Fingered Discount, researching this would take her back and forth across the Atlantic from her home in Brooklyn to her homeland of southern Italy.

Those trips plunged her into a culture she didn’t yet understand, but she took the time to see from their perspective. “I read everything I possibly could, and it really did shine this light on what the culture was like: century after century, millennium after millennium of being put down” she told Eugenia Williamson. She also discovered the impoverished lives of the Italian farm workers, the drive to find a new home in the promising “land of the free,” and the deep distrust the United States held for all those immigrating not that long ago.

The resonance was not lost on her, and it was personal. Without her great-great- grandmother’s perilous voyage, where would her life be now? She told the New York Post “she was really our saving grace. She was this heroine. And I think that’s what most people whose immigrant families came over can take away from it. I think that applies to everybody who lives in America. They need to look back and see where they came from.”

Vita landed in New York Harbor in 1892. Just a few short years later, the Immigration Act of 1924 was passed to severely limit the number of Southern and Eastern Europeans (mainly the Italians and Eastern-European Jews) entering the country. It was successful.

In researching her book, Stapinski discovered the racist pseudoscience that helped lead to the Immigration Act and it struck a nerve. Cesare Lombroso, an Italian doctor, had proposed the idea of a genetic criminal and described in great detail their appearance: “the natural born killers” looked exactly like the many Southern Italians immigrating to the United States. They looked like her family. And so this was who got blamed for the rise in crime and unemployment at the turn of the century.

Sound familiar? In a recent op-ed in The New York Times Stapinski did not pull punches. Researching her book had drawn her closer to her own history, and also the struggles and stories of the thousands of Italians who had made the journey alongside her forebear. “Italian-Americans who today support the president’s efforts to keep Muslims and Mexicans out of the country need to look into their own histories — and deep into their hearts. After all, they’re just a couple of generations removed from that same racism, hatred and abuse. Had our ancestors tried to come days, weeks or months after the 1924 ban, we may not have even been born.”

““This book is many things: a gripping murder story, an ancestral journey, a tender yet funny reflection on motherhood and love of country, family, and food. But mostly it’s a total page turner.””

An Excerpt from Murder In Matera

They boarded the third-class compartment with a couple of sacks, one with a bit of bread, maybe some small pears. Vita sat on the hard wooden seat by the window, with Nunzia on her soft lap, Leonardo by her side, and watched Grieco and the world they knew, the lonely landscape of home, slowly fall away.

The first stop on the train was Ferrandina, where the killing had happened. Vita was happy to see it pass by her window for good. Vaffanculo, Ferrandina, she probably thought. Good riddance.

Tiny, mumlike yellow wildflowers lined the tracks between the stations. Vita didn’t realize that one day soon she’d miss them. And the sheep in the distance past the town of Baragiano, a pastoral scene she would never see in Jersey City. How could she know that mountains and fig trees and shepherds would be replaced with factories and smokestacks and cops walking the beat?

The sheer cliff face rose up near Bella-Muro, which meant Beautiful Wall. And it was, this cliff, it was beautiful, as was the stream that flowed at its base, filled with chalky rocks and boulders, a landscape Vita had taken for granted.

They watched the craggy Lucanian Dolomites rise like giants in the distance, and made their way past bare-faced hills and tall cypress trees. They passed through Eboli, the place where Christ had stopped in Carlo Levi’s book, where civilization ended. But Levi hadn’t even been born yet, much less passed through here and written his masterpiece. In Torricchio, the train snaked through pointed pine-covered mountains and dipped into low, green valleys. They sped through forests where brigands had once hid out and stashed their kidnapping victims. Where treasure was said to be buried.

After about ten hours, after what seemed like 1,001 stops at every coastal village along the way, Naples appeared in the distance, announced loudly by blue Vesuvio, its top covered in wispy white clouds. Was it smoking? she wondered, fearfully. But its clouded peak was quickly forgotten as she stepped off the train into the city.

What a circus. It was churning with madness, with toothless beggars begging and train conductors in blue uniforms shouting and carabinieri in capes and mustaches giving orders and the big, shining duomo in the distance and palm trees and the manicured park and the horses and buggies with their drivers in tall hats. It was too much to take in all at once, and Vita feared she would fall into one of those stress-induced states, where everything would go numb and she would cease to function. But she held it together. She squeezed Nunzia’s hand so tight the girl cried out as they marched into the madness, my young great-grandfather Leonardo happily, bravely leading the charge.

This was their first lesson, a good lesson, to prepare them for the insanity of the New World.

She and the children asked the conductor which way, which way to the harbor and he pointed. But it wasn’t necessary. Half the train’s passengers scrambled to the same spot, through the grand arches of the train station, under its stone balconies and giant clock. Vita was just one of 61,631 Italian immigrants to travel to the United States that year.

They made their way like a river of bodies day after day through the crowded streets, past tall buildings, five, six, seven stories high, with French-style wrought-iron balconies covered in laundry, shirts and skirts and underwear strung across side streets where the buildings nearly touched one another. So much laundry. so many people. How could so many people live in one place? A half-million people.

Vita and her children walked the two and a half miles to the harbor, past Garibaldi Square, now with the big statue of the hero in his caped uniform, leaning on his sword. They made their way past the curved square known as the Four Palaces, whose buildings were held up by giant men made of stone. Vita had never seen anything like them. They looked so real she expected them to break free and come down and speak to her, to point the way to the port. Most spectacular of all, though, was the newly built, 22 million lire Galleria Umberto I, the long glass and metal-ribbed wonder, with its huge dome and four offshoots, the whole building shaped like a giant cross. It ran 160 yards from Naples’s main street—the Toledo—all the way to city hall. Massive angels, wings spread, floated just below the glass ceiling, five stories high. How did they not fall and come crashing down on their heads? How they floated up there, like real angels!

And just when Vita thought she could never glimpse anything more wonderful than that, they arrived at the port, the beauty so intense it caught her breath. Too beautiful to describe really, with the blue island of Capri floating like a big slipper in the distance, and the green island of Ischia, and the great rocky castle at the water’s edge. At sunset, the islands turned purple and the houses at the foot of the mountains blazed orange in the dying light. It was so gorgeous, tough little Vita nearly cried.

Italy had been cruel to her and her family. To everyone she had ever known. But this, this was the cruelest of all, seeing the most beautiful scene ever before leaving it for good. See Naples and die, went the saying. And now she understood it.

Italy was like a lover who was so gorgeous, he could mistreat you whenever he liked. But a woman could take only so much. Vita would leave and never look back.

And now there was a new lover, America, more beautiful and much kinder. At least that’s what she’d heard.

Though Vita had no idea what to expect, exciting things were happening in America that year. Not all of them good. Labor strikes had broken out that summer, including the Homestead Strike among Pennsylvania’s steelworkers, in which ten men were killed. In Wyoming, farmers were going up against the big ranchers in the Johnson County War. And in Oklahoma, a hundred men—mostly Italian immigrants—would die in a mine explosion. When some black men tried to help rescue the survivors, they were threatened with rifles.

But in Vita’s future home state of New Jersey, John Philip Sousa’s band was making its debut with its patriotic marches. The first American-made car was taken out for a test drive. And the Pledge of Allegiance, written over the summer by a Baptist minister, was published for the first time and would be recited by millions of schoolchildren in a few weeks, that following Columbus Day, words that no one had memorized just yet. They were like the words to a new prayer that the immigrants wanted badly to believe were true.

…One nation,

Indivisible,

With liberty and justice

For all.

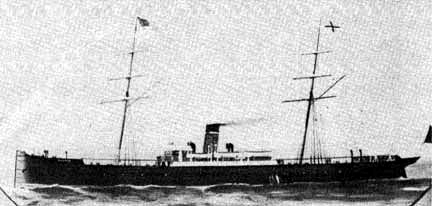

The Neustria