Twenty Six Miles

The marathon race is a transnational signature of courage. It is mankind’s one of a kind undertaking. An invitation to test one’s inner strengths, both physical and psychological. An opportunity to fulfill a promise.

I grew up in Afghanistan. Education was on my mind as survival. I wanted to go to one of the best universities in the world if I could finish high school during wartime in Kabul. One day when I had left school, I had seen men with beard and bandana guarding government building with big rifles and RPGs. The subsequent internal wars sent thousands of families including us to neighboring countries in search of safety. In Pakistan, I made carpets to support my family, but the dream of getting a good education never left my consciousness, even after returning to Kabul alongside American troops and becoming refugees again in Pakistan for a second time.

During those distressful days when an angel appeared to us and told me he would help me get to a university of my choice, I not only believed him, but I already begun thanking how to thank him not just in words, but with an extraordinary action.

I thought about such an action for weeks after I arrived in Boston to attend college. One day when I walked down from my hillside dorm to get pizza and noticed a flock of college kids in athletic outfit jogging on Boston Ave, I saw a perfect opportunity to fulfill my promise.

I joined my school’s Presidential Marathon Challenge. Led by Tufts then President, Lawrence S. Bacow, and Tufts Athletic Coach, the loyal Don Megerle, the PMC gathered more than 200 Jumbos (Tufts students) to take on the challenge, and, on the side, fundraise for several medical programs. We trained for four months part of the six-month training; quite a challenge for someone who grew up in Afghanistan where people did not really run or when they did it was for security reasons. The culture didn’t exist, neither did treks and trails. The air was polluted, and people were judgmental of such “alien” activities. Running was impossible for women.

The sights and sounds of the Mystic River we ran around in the early morning twice a week was refreshing to my body and spirit. It was extra fun to see President Bacow, who is now President of Harvard, himself join us on practice days. I remember he always told us to watch out for the “black ice.”

Among challenges I faced was the lack of proper shoes. When Coach Don checked my sneakers and told me they were expired six months ago, I was surprised that clothing too expired in America. The run was grueling to say the least. At one point I was so hungry I wanted to eat the volunteers who held energy bars out. When I tell that story to my friends, they think I am joking.

Running the Boston Marathon to thank my benefactor and to experience freedom and being part of the modern life was so fulfilling I decided to immortalize it. I wrote a short story based on that adventure. Go Ned Go! is available on Amazon. It is one story in a serious of short stories that cover the most meaningful aspects of the tumultuous youth I was allotted in Afghanistan. The memoir takes the reader along the grueling twenty-six mile on which the narrator learns something beyond the ecstasy of a promise fulfilled.

AN EXCERPT FROM “GO NED GO!”

The race started off like the beginning of the college parties I was getting used to, loose and festive. Overtaken by excitement, I sprinted ahead, leaving Felix behind, then slowed down, remembering that the turtle had beaten the rabbit.

I was elated; being carried along by the sheer force of the phenomenon.

I looked to the sides and saw spectators under colorful umbrellas and ponchos, cheering. I saw racers of all ages, sizes, and shapes. A woman was wearing a funny hat. A muscular man had stuffed himself into a silly pink skirt, and there was a gigantic head of a roadrunner, the bird I recognized from watching Looney Tunes back in Kabul.

I stayed abreast with Felix, out of courtesy, mimicking his slow-but-steady strategy. I knew when the time came, I would wave good-bye to him, and sprint away, finishing before him with an impressive time.

“So…” Felix said. “What motivated you to run the Marathon?”

Felix was a graduate student from Vermont, studying music; the first student I had spoken to on campus. Six feet tall like me, he sported an untrimmed beard with streaks of auburn.

“Oh man.” My breath was white vapor. “It’s a long story.”

“And we have a long way ahead of us.”

“True.”

I took another lungful of the frosty air, remembering that long-ago phone call from Mr. Ned Colt in Islamabad. “So what’s your schedule like tomorrow?”

“I’m indebted to someone,” I said to Felix. “And I’m running to give thanks to him.”

“Hmm,” he went. “So he’d be at the finishing line to collect his loan?”

I laughed. “Angels help without the expectation of anything in return.”

Felix nodded, the corners of his mouth pulled down. A semester of cohabitation and I had learned that getting deep or personal would not keep him engaged. Felix was focused. He saved his mental energy for writing and playing music. He was attached to the piano the way an infant would be to its mother’s bosom. “I see now why you needed duct tape last night.”

“That’s right.” I thumbed at the grey tape plastered across my chest.

“And what’d he do exactly?” Felix pressed on.

In my mind, I saw Ned standing inside our rental in Islamabad two years prior. His looming presence. The tan he’d soaked up covering the Middle East for years. Eyes that had grown only kinder after witnessing so much hardship and enormity in the region. And I pictured his broad forehead, the embodiment of wisdom and blessings accordingly to my culture.

I inhaled and exhaled. “Let’s say,” I said to Felix. “At the very least, he saved my life. Can you say it like that in English?”

“Sort of,” Felix muttered. “What more can someone do for you than saving your life?”

“Much more,” I rebutted. “Saving your family, your good name, and your honor.”

Felix nodded to signal he understood and changed the subject. “Did you meet your fundraising goals?”

“Only half,” I said. “Five hundred bucks.”

“That’s good.”

“What about you?”

“Twelve hundred,” he said. “Two hundred extra!”

Of course, I thought. You are established. You are an American. You were born here. You have connections.

“Where will your donation go?” Felix said.

“To medical research.”

“Me too.”

“And why are you running the Marathon, Felix?”

“It’s fun,” he said abruptly, scanning the grey that was threatening to darken further.

I too checked the sky. The few openings of blue were being swiftly swallowed up.

I regrouped my thoughts to focus on the long journey ahead. I was checking out the runners at my pace, passing a you-can-do-it nod, when a cold alarm clutched at my heart. Would it happen again? A locked knee? The hell was that?

A week ago, during our last practice, 18 miles, something strange had happened to my body. At mile 16, my knee had locked. I was holding the two sides of my left knee. I rubbed it hard, but it was stuck at a right angle like a carpenter’s steel square. Holding the sides of my knee, I had pushed forward, hopping on one leg. To stop was death.

“Hold it!” A voice had thundered from behind. It was Coach Maggio shouting from inside his patrolling van. “Did your knee lock?”

The Coach had said it as if getting a knee locked was just a routine.

“Yessir,” I had answered, hopping and kicking. My locked knee didn’t hurt; it was just weirdly swollen.

“Stop!” he had hollered, sticking his head out of the window. “You can’t run anymore.”

My heart had skipped a beat wondering how long I would be grounded.

Coach Maggio had helped me get into his SUV, then to a physical therapist on campus, warning me that he may not be able to clear me in time to run the race. I hadn’t said anything. I knew I would run the race even if I had to hop the twenty-six miles on one leg.

“Around mile six,” Felix reclaimed my attention, “there will be water and snacks.”

“Not at mile 2?” I shot back. “I’m hungry. I didn’t have anything in the morning.”

“What?” His head turned abruptly, taking a good look at me. “You didn’t eat anything this morning?”

“No,” I said. “And nothing last night.”

Felix almost stopped; then leapt forward, mouth hanging open. “You must be shitting me?”

“I dunno,” I said. “I was busy finishing my paper.”

“Dude?” He shook his head and said nothing.

“What?”

“And you think you can finish?”

“Oh yeah,” I blurted with a gusto. “I will finish.”

“I was advancing ahead but my mind was reverting to past when we had become refugees for a second time.”

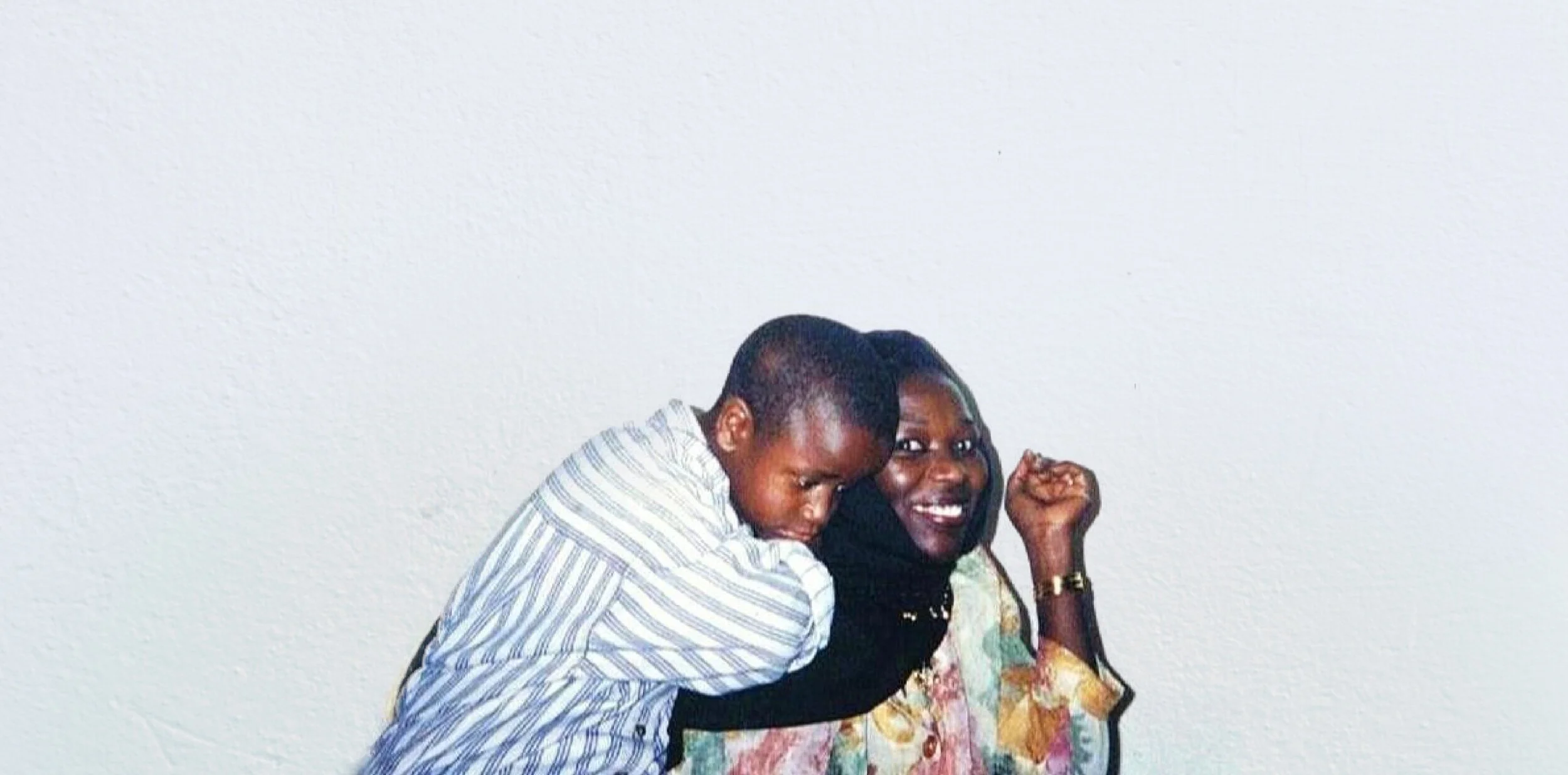

Images of Ned reappeared in my mind. He was opening the first box. The label read Marriott Hotel, perhaps where he stayed. I saw my mother nodding a thank-you to Ned, looking at the two hundred dollars banknotes in her hand. Twelve thousand rupees would go a long way until my father arrived with cash.

“We are only entering mile 2,” Felix said, grinning with concern and pity.

“I will finish this, bro.”

“Don’t kill yourself.”

I chortled and looked out at the strobing trees. Do or die running.

“It doesn’t bother you we didn’t get to register?” I shot at Felix.

“Nope,” he said. “It’s not about having an official record, is it?”

“It will be recorded somewhere,” I said. “Our voices, our images, everything emitting out of reality, the good and bad we do, stays somewhere in the universe. Forever.”

Felix was mute for a long moment, and then said, “And does it bother you we didn’t qualify?”

“Nope,” I said. “It’s just for me. And that’s amazing we got in through our school.”

“Yup,” he said, making a dramatic move with his arms. “Race?”

I chortled. “I thought you were the least competitive person I know.”

“Are you sure?” he said, lunging his legs and arms wider.

I felt a surge of electricity, provoked, taking him seriously, and sprinted ahead of him.

“Slow down!” I heard behind.

I did.

“I was joking,” Felix said. “But it’s true I’m the least competitive.”

We resumed our steady pace. And the moment we stopped talking, my dormant worry resurfaced. Is it going to happen again?

No matter how cold, I would make it; no matter how hungry, I would put up with it; and no matter how tired, I would push my thirty-year-old body to its limits, but if my knee locked, it would be an unfortunate “technical issue.”

“God damn you knee!”

Felix’s head turned. “Are you okay?”

I recalled our science professor’s complaint about evolution getting everything right, but the knee. “It’s the worst design ever,” the renowned scientist had said.

“Just thought about my knee last week,” I said, pointing with head at my left knee reinforced with bandage.

“Don’t think about it.”

I tried not to. “What did you have for breakfast?”

“And don’t think about food either,” he said. “Two protein bars.”

“Go Ned Go!” A collective clamor hit me in the head from the sideline. “Go Ned Go!”

I looked at a group of five to six women sheltering under three conjoined umbrellas. I waved at them as a newfound stamina infused all over my body, snuffing out my thoughts and worries. My stride became wider; my smile grew bigger. I loved these women. They felt like my buddies, like the family I didn’t have around to cheer me on.

I ran faster and left Felix behind.

I was advancing ahead but my mind was reverting to past when we had become refugees for a second time. Dammit. The first time made sense; we had fled the internal wars that razed down the city, claiming countless lives. Our own home was hit by a rocket launched by the Gulbuddin mujahideen just a week or so after we had vacated our house. We would all be dead if it wasn’t for my mother’s defiance of my father’s desire to stay. But why did we have to abandon our homeland — for a second time — when the international community had begun rehabilitation, when hope had beguiled, especially, city dwellers?

I let a sigh out and looked up. A raindrop from the Boston sky fell straight into my eyes. The quick shot of energy from the cheerleaders had long abandoned my limbs.

Others had left Afghanistan because of the Taliban attacks and American bombing, but we were forced to leave for a different reason. My sisters had become too visible in the eyes of the ultraconservative with turbans and the prejudiced wearing neckties. There was no place for us in Afghanistan anymore. Society was crushing our spirits and squashing our desires for freedom. My dream of Afghanistan becoming Switzerland had vaporized.

“Dude?” Felix caught up with me. “Don’t run too fast until you’ve eaten an energy bar on the way.”

I exhaled, cheeks puffed up. “He entered our lives at a time we were dying.”

“What?” Felix breathed. “Oh, Ned?”

“Imagine,” I continued, “someone grabbing your hand as you are hanging off a cliff at the moment you are about to let go because you have had enough.”

Felix was quiet. This time I wanted him to hear me out.

“But it is not only your weight pulling you down,” I said. “But it is also the weight of your family who are hanging onto your legs. And you cannot let go for the sake of your family. You know what I’m saying, Felix?”

Felix’s eyes were focused straight on the road.

He didn’t have to reply, and it did not bother me; we foreigners and immigrants had come with lots of baggage, baggage whose content only we were familiar with, and only we could fathom.

Why me? Why my sisters?

“Let’s hit it!” I bellowed, overtaking Felix again. My brain was telling me to be the turtle, but my legs were running as though I was escaping Afghanistan, running as fast and as far away as I could.

I moved past many runners and kept pushing on. Soon I spotted volunteers and realized it was mile 6. There were tables covered with plastic tablecloths on both sides of the road, offering water and juices. My eyes searched for food. Without slowing down, I reached a table and snagged a cup of water. Then another from the next table a few yards apart.

I looked behind and was surprised to spot Felix among the runners. I thought the most he could do would be to catch up later, perhaps halfway, around mile 13.

“You are the turtle,” I said.

“And you shouldn’t be the rabbit,” he said. “Don’t fall asleep on the way.”

We laughed.

We ran without talking for over half a mile. More tables appeared. We snagged water and energy bars without slowing down. It felt good. Everything seemed to be going according to plan, a plan I did not have. Planning meant eating properly and registering.

“You know what’s good about not eating, Felix?”

“Quitting sooner than you have to?”

“No dude,” I said. “You don’t have to stop for the bathroom.”

“Ha.”

In seconds, the energy bar had turned into functional fuel, reenergizing my legs.

I sprinted ahead. Felix was nowhere to be seen. Then I slowed down to find him, zigzagging between other runners, but Felix was gone for good this time.

After a mile or so of vigorous pushing hard, trying to locate Felix among the runners ahead of me — though that would surprise me — my body called on me to conserve energy. I did so without losing my momentum. I was now pacing people who looked like serious runners. I thought I was not behind the sea of people, but in the front of them, right behind the elites.

“Go Ned Go!” A shout blasted like fresh air from the flank. I picked up the pace, conscious that it was not energy from the energy bars but empowerment from these spectators that reinvigorated me, the power of a friendly gesture from my new society.

Memories transplanted me back to my birthplace. I let a few tears run down my cheeks. I shook my head. These folks wanted me to run forward; those back home wanted us beneath the ground.

I loved the cheering. I was too ecstatic to tell them I was not Ned. I looked down at my feet. My sneakers still looked like new. At the beginning of our training, Coach Maggio had checked our running shoes. Mine had expired. I did not know shoes expired like food did. Back home, neither foodstuff nor footwear did. Comfort was not a concern and unsightly holes got patched. I could not train for a couple of weeks until I shared my technical problem with my Academic Dean. She had handed me money to buy new shoes. I had and they felt good.

I shook my head, again. Unlike my own compatriots, everyone here wanted me to move on.

My eyes searched in vain for Felix. Now that I had lost him for good, I might as well finish with a personal record. But, then and there, I was reminded my knees might get locked.

I pushed back my fear and pushed forward. Do or die running.

“MSNBC!” A young guy hollered. “Go Ned Go!”

I waved at him, then gazed down at the duct tape.

I picked up more water and was about to grab a food bar when another runner snatched it right before I could. I didn’t stop or return to get a bar. I went for more water at the next table. Liquid or solid, something had to go inside my stomach.

Along the way, when hunger hit me, I thought about Ned, and the emptiness would disappear. It was magic. I was growing proud of myself. Every stride was a yard less to my goal.

Mile 11. I began to feel it. The eleven mile mark was the furthest I had trained when going solo. But today was no practice; this was a test of who I was.

My body was caving in. I took a lungful of the frigid air and lifted my chin up, facing into the drizzle. I brought the image of Ned Colt to the front of my brain, telling myself over and over again to keep going.

“I’ll come by at eight PM then.”

Why did his voice have a healing power? Why would a stranger feel so close? We were even hiding from our relatives. Everyone was out to destroy us and we were not paranoid; we had carried the invisible arrows that were stuck in our hearts to Islamabad.

I kept running, recalling the threatening phone calls my sisters received a hundred times a day, the leaflets they showed me in absolute hysteria. “You have brought shame on our Islamic society. You will all be soon sent to Hell.”

And there he was, Ned, on time, as punctual as a khariji Westerner would be. Exactly at eight o’clock. I had escorted him upstairs. He had visited my family before in Kabul; when my sisters had started making international headlines, when my mother had made him my favorite dish, aushak, raviolis stuffed with leeks.

The khariji reporter had learned a few Farsi words. “Salaam,” he had said, smiling cautiously, sitting cross-legged with us around that depressing dining tablecloth, speaking only when spoken to. An Afghan’s distarkhwan must have sufficient food no matter how poor he is. Save for water, ours had nothing, not even tea. We were not embarrassed. If we had to explain, we would. Our mother had spent all our savings to secure this rental in Islamabad so we would not end up in a refugee camp, miserable, arms sticking out for handouts from the United Nations.

“So, you want to go to college?” Ned had picked up the conversation I had started back in Kabul a year ago in which I had shared a burning desire to study in America.

I had nodded, licking my lips for any residue of the fluffy confection.

“Here it is,” he had said, opening the second box.

Everyone had craned their heads, staring at Ned’s hands holding two thick books. “Start here,” he had said. “I will send you whatever you need to prepare you for college. I’ll pay for your flights if you earn an admission.”

My life had changed instantly. I held one book. The SAT. Standard Aptitude Test. 10th Edition. I flipped through random pages. Then I threw the book up and down to weigh it. Part of me still flickered with a sense of humor, and I wanted to show how heavy it was, and that I could master it, but nobody had laughed.

The second book was Mathematics. And that was impossible to tackle even if I had lived a happy and productive life until then. Math was not an Afghan’s forte.

“I will learn this,” I had said in a promissory tone. “I will get this done.” I had looked around at my sisters, telling them with my wild eyes that if I graduated from school in America, I would become someone, and then I would bring everyone to a safe place.

“Go Ned!” I saw a Bostonian couple yell at me. “You can do it!”

I took a lungful of air, waving and smiling at them, my mind lingering in Islamabad. Ned Colt had taken me by cab to the US Education Foundation in Pakistan. He had introduced me to the counselors as a “bright student” with “good grasp of the English language.” He had introduced me to another angel; Ms. Zarene had warmed my heart by taking a personal interest in my case, editing my personal statement, showing me how to win a four-year international scholarship.

Mile 13.

I passed a knot of runners I thought were just behind the elites. But there were no elites to be seen; just more commoners like me, but with sophisticated, professional sporting gear.

Then came mile 16. I was in disbelief for surviving that long, remembering the Afghan expression, gosh-i shaitan kar, or knock on wood. At the same moment, I felt a crack in my leg, and instantly went down as if getting shot by a bullet. It had happened. My knee had locked.

I felt dead inside.

I grabbed my knee. “Please!” I screamed. “Not today; not now, please!”

Do or die running.

I ran every possible solution in my head and there was only one; I needed a functioning knee to run. I tried to trick my mind or body or both to do whatever they could do to keep me going. I replayed screams of “Go Ned Go!” in my head, but my knee felt like the bulging joint of two metal rods welded together. Tears blurred my sight. I rubbed my hands on my knee frantically as if trying to start fire.

I watched dozens of runners pass me. My tears were now mixing with the rain. I crouched on the street, defeated. No, no, no, this cannot happen now; not today, Goddamnit, not today.

“What’s your schedule like tomorrow?” I heard the words so loud in my ears it was as if Ned was standing beside me. I looked around. Felix was nowhere to be seen. It was like the Judgement Day I had heard back home: The sheep would be hanging by his leg, the goat by his.

Damn, you knee. If I could not keep this promise, how would I keep my bigger promise of rescuing my sisters?

“You have a good grasp of the English language.”

His smile radiated goodness; his eyes ratified a sweet soul.

“You will do well in college. You’re a smart guy.” “What’s your schedule like tomorrow?” “…schedule like tomorrow?” “…schedule…”

Someone had respected me. I was someone. I was worthy of that generosity. I deserved an education, and perhaps peace of mind away from a place that had tormented me almost out of existence.

“I will come by at eight PM.”

A frisson of fortitude restored me. My chest swelled. I was hopping on one leg, rubbing my knee, clutching onto that night in Islamabad like a drowning man clinging to a life raft. Suddenly, I felt Ned beside me, his stature and his wide forehead, as though he was running along with me. “Eight PM is it!” I let myself howl on the streets of Boston, feeling a new surge of stamina.

I stood up.