Ya Oummi

I'm not sure what my mother expected when she first moved to America, but I can certainly tell you what she did not anticipate; raising four boys as a single mother living on welfare was not part of the plan. It became her reality.

My mom's hopes must have been severely crushed if she envisioned a white picket fence, private yard, and fancy car. I could not detect any disappointment when I was a child. Or maybe I only heard her express her overwhelming frustrations whenever she complained in Arabic, before I could understand the language. My mother never got to taste the pie that exists in the minds of most immigrants that come to America. However, her identity fits into this country’s narrative because people like my mother make it possible for the American Dream to exist in the first place. Historically, the United States has always viewed and used immigrants as a cheap source of labor - but I digress.

My mother is a poor, black, female immigrant; she embodies every element that America hates yet needs to survive. I like to see her story as part of a broader lineage of women who arrived in this country, by choice or force, and did what they could for their families and communities. I am forever grateful for what my mom did for me. I cannot quantify the good deeds she's done, let alone pay her back. She set an example of how resiliency and ambition can overcome terrible situations. Although I learned many good things from her, I would be lying if I said my mother's mistakes and shortcomings did not teach me a lesson or two about life. More than anything, my mother served as a prism of America's peculiarities.

My mother met my father sometime during the 1980s. He was a charming and handsome African-American teaching English in Sudan. She was a young beautiful Sudanese woman who was college educated, a rare thing at the time for a lady from South Kordofan. She caught his eye while she was present at his workplace. According to my mom, he expressed to a mutual friend that he needs that "beautiful African queen" or something else corny along those lines. I'm not sure how long it took for my father to win her over, but I imagine there were some hurdles he had to jump. During my second visit to Sudan when I was 20-years-old, an older relative described my grandfather's hesitancy to see my mother with my dad.

"Things would've been easier if he were darker like you and from the Nuba tribe," she said.

My father is not fair-skinned by American standards, but he lacked that majestic dark tone that characterizes the people of South Kordofan, the Blue Nile, and South Sudan. Keep in mind that he was a foreigner, so he was seen as an outsider by my grandfather. However, things worked out, and my parents got married. My older brother, Umar, was born in Khartoum in 1990, and the three moved to Houston, Texas. Eventually, my mother had me on May 3, 1992.

Although she was well-traveled before meeting my father, Houston was radically different from my mother's native country. She had to adjust to a coastal capital where she found African Americans, Latinos, Asians, and Anglos living together. When I was a child, I remember how my mother stood out whenever we walked outside because she was the only woman wearing a hijab. Mama remained faithful to her culture despite being thousands of miles away from home.

Regardless of our American surroundings, my mother did everything in her power to ensure that we were children of the Nile. Sudanese folk music played loudly at home, along with R&B vibes. Kisra and asida were adjacent to our soul food dishes. And of course, I cannot forget how my siblings and I had to call every female adult khalto (aunty) & and male adult khalu (uncle). My mother communicated with us using an Arabic-based creole that combined the poetic rhythm of the Sudanese dialect with English.

She would say phrases like, "Ya Muhammad, imshi hnak, and bring me my purse!"

I also became familiar with expletives that my mother would spew whenever I acted out of line.

At times, malicious circumstances solidified our Sudanese identity. My older brother and I often got into fistfights with the neighborhood kids who made it their duty to remind us that we were different from the rest. Notwithstanding my American citizenship, children yelled, "You’re an African booty scratcher!"

American antagonism towards Sudanese people went beyond petty bullying. I recall witnessing my mother sobbing while Bill Clinton addressed the American public on television after his administration bombed the Al Shifa pharmaceutical factory. America's decision to decimate the factory in 1998 devastated Sudan's public medical services. My mother's tears, like the bruises on my hands, indicated that my birthplace was not accepting of our foreign heritage. To make matters worse, the man who brought her to this country would go astray.

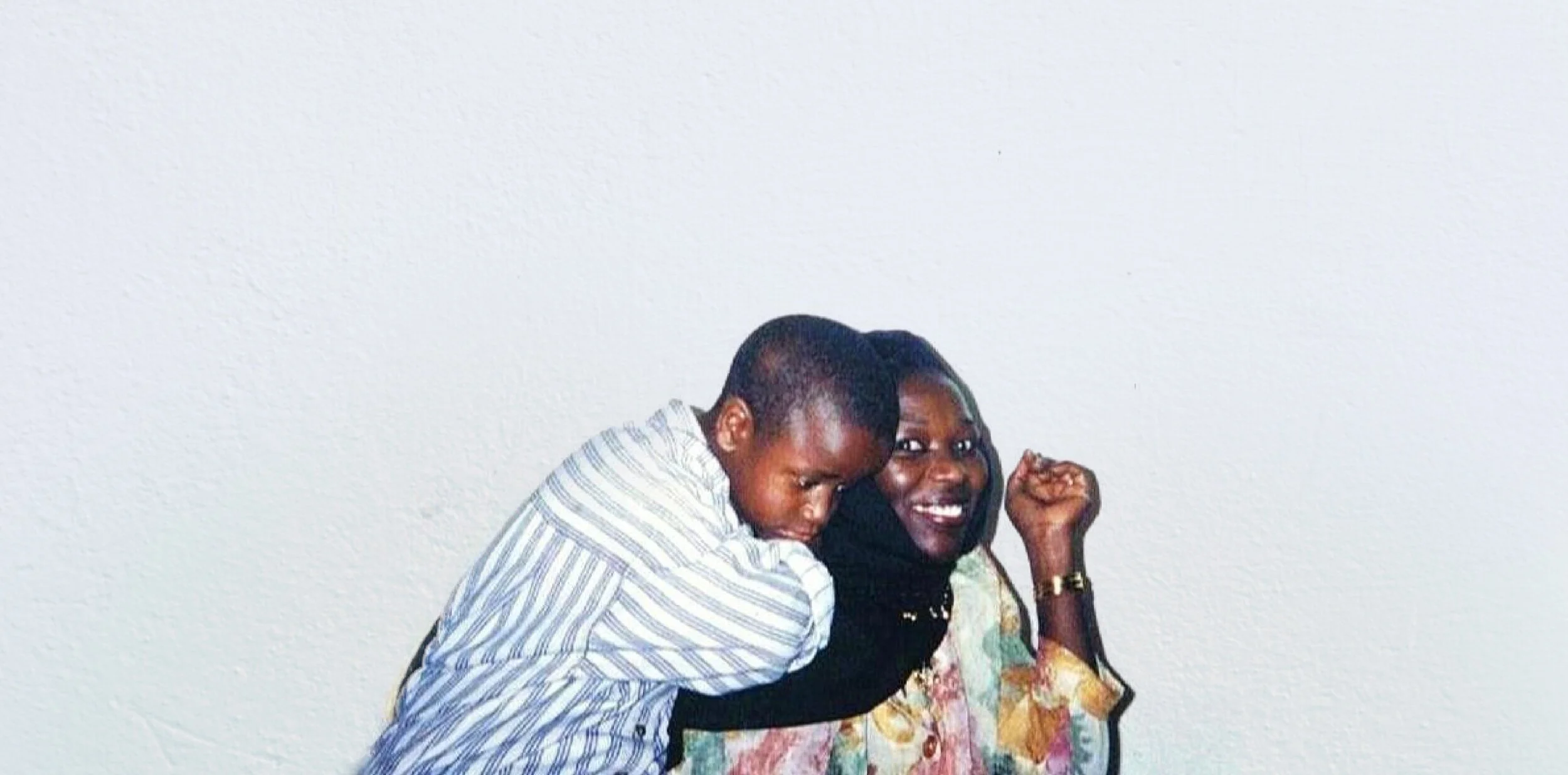

the author’s mother, center, in Khartoum

I still remember the day my father left us. It seemed so abrupt because, at the age of seven, I was unaware of the turmoil happening at home. School hours shielded me from seeing the arguments and domestic abuse. My younger brother wasn't attending school yet, and he vividly recalls the day he saw my father's hands around my mother's throat. Before she knew it, my mother became a single mom raising four boys with no supportive spouse. None of her family members lived in the Western Hemisphere, and in the land of dollars and false hope, mama did what she could.

We had to find a new apartment and go to another area because the rent was too high. During those long drives of moving, mom would say, "Ya Modibo, hold the cold bottle on my face." The low temperature of the water helped keep her awake as she drove throughout the night. Despite everything, memories of our struggle are not painful to think about because my mother never allowed my brothers and I to feel the sting of poverty. There was not a time when we went to sleep hungry, but I cannot assume the same for mom. My father's lack of responsibility and empathy weren't the only factors that put us in those circumstances. My mother's degree, which she received from one of Sudan's top universities, did not count in America. Like many immigrants of her generation, she had to start from scratch because her educational background was irrelevant as far as Uncle Sam was concerned.

In 2004, my mother and I experienced one of our most fond moments in memory. I won third place in the B.A.S.I.S. National Geographic Bee. I lacked formal training, but my childhood curiosity carried me throughout the competition. Looking back, I do not doubt that xenophobia drove me to seek knowledge about the countries outside of America at such a young age. Anyways, my mother was ecstatic about my accomplishment. She loved it when any of her children did well. Academic performance was the currency we paid for mama's hard work, and I loved seeing her smile.

My mom bragged about my victory at the National Geographic Bee to an old white man named Douglas, who employed her as his caretaker. He was a former professor at UC Berkeley who taught geography in college. Shortly, my mother brought me around Douglas, who showered me with praise. I was too young to care for what he thought, and I still do not hold his words of encouragement in high regard. After he passed away, my mother admitted that Douglas confessed to harboring racist views towards his former students who were African-American.

"He told me that he never gave a black student an A, even when they earned it," she said.

I was much older when she told me. Frustration consumed me. Black students were denied a particular grade because of the color of their skin, and a financial chokehold forced my mom to take care of a bigot. I did not know which part irritated me more. However, I was not shocked by what my mother told me about Douglas. After all, a racist white man relying on the labor of a black woman is as American as the Star-Spangled Banner.

My mother has now spent almost three decades of her life in America. She managed to put three of her four boys in college, with me being the first to graduate. While taking care of us, she also earned a master's degree from Mills College. Despite making a lot from nothing, I'm convinced that my mother is not satisfied with how things turned out. Her children aren't as "accomplished" as she expected us to be (my mother anticipated a doctor, not a freelance writer out of me). She lost her youthful years to parenthood, stress, and tears. Mom's life in the states is a far cry from her pre-married life in Sudan as an accomplished bachelorette who had the luxury of traveling and putting herself first.

Of course, my mother would never explicitly express her regrets. She cannot accurately communicate her pain due to sexism. Women are the piñatas of patriarchy, and many times they internalize patriarchal standards. Therefore, my mother will always find solace in motherhood because she fulfilled her role in what should've been a "nuclear family." I'm convinced that deep down, she wishes she never got married to my father.

My mother's story is not unique. I'm pretty sure a fair share of millennials with immigrant moms would snap their fingers to her story. My mother and I can disagree on a million things, but I remain thankful for what she's done for me.

I used to yell “ya oummi” as a child whenever I needed something from her. The phrase means, "oh mother" in Arabic.

"Ya oummi, ya oummi,” I'm forever grateful.