Mirror Door Whore

Vietnamese who live in-country refer to those in the diaspora as Viet kieu – sojourners, those that wander. The label conjures ghosts, free-floating and aimless, robbed of destination and forever yearning. Those ghosts wander because the living are ambivalent about co-existing with them. I was one of those ghosts, living for years in the soft purgatory of a certain kind of first-generation immigrant: too young to have rooted loyalties in the homeland, too old to forget it, comfortable in all lands, uncertain where I should settle.

I brought my husband David to Vietnam for an adult gap year in 1998 – between my medical residency and fellowship. He had a Fulbright, and I had talked my way into a job with an American non-profit working on reproductive health. I was the first in my family to return to Vietnam since we fled in 1975, on an ill-defined quest to claim what I could of my early childhood memories of Saigon, and family history that my parents would not or could not share with me growing up in America.

I would be the first in my family to return. My father was the only son of the first wife of the village chief in our ancestral hamlet. That made him the village chief in absentia, and me his representative. Contemplating doing all this with my grade school Vietnamese wound the muscles in my jaw and neck, and whittled my sleep to a few desperate hours a night in the weeks before our plane finally took off.

We searched for a house to rent in the colonial heart of Ho Chi Minh City, the cobblestoned square of alleys just far enough from the city core to buffer the thrum of tourists. Among its spindly walkways, we found a three-story row house newly painted yellow, furnished with pleather settees, carved wooden beds, and a clothes washer, an amenity only found in houses on our side of the alley where expats rented. Across the eight-foot alley stood older, squat two-story structures with darker rooms and no air-conditioning, where the landlords and northern Naval officers and their families lived. Echoes of clanging pots, scraping chairs, and conversation ricocheted down the air corridor between the alley walls, hitchhiking one on top of another with such clarity that it was impossible to tell if a spousal argument we heard was happening next door or eight houses away.

An implicit set of expectations ruled decorum between Vietnamese and expats in the neighborhood. Europeans, Australian-New Zealanders, Japanese, Indians, and Americans would behave as became the moneyed and privileged, divulge minimal information about their professional activities, and serve as an important revenue source by hiring locals to buy and cook their food, chauffeur and nanny their children, clean their houses, or serve as interpreters. In exchange, Vietnamese would honor a respectful distance, exercise discretion, and offer tips on how to navigate the bureaucracy required for amenities like Internet access or buying a car.

Growing up, my parents had adhered to their own rules of distance. Questions about life before Philadelphia, where the edges of family extended beyond my mother’s relatives who had immigrated with us, about Vietnam or what my parents brought of it to America, were met with silence, a sudden agitation from my father, or nonsense murmuring stretching away from the conversation. In our house, the war was crated and warehoused; if we wanted to learn about it, we were on our own and could count on their hindering us if they knew we were looking.

So I had collected clues whenever they were dropped and hoarded them for future sense-making. I noted postmarks on letters in thin blue air-mail envelopes, some coming regularly from Ho Chi Minh City, some from unfamiliar places in Vietnam, and a rare one from Canada or France; I watched how my parents received envelopes from Vietnam with anxious faces, but the ones from Canada with smiles.

I learned that the mail went in the opposite direction too. I helped my parents pack boxes with bottles of Tylenol and vitamins to send to both north and south Vietnam. They wired cash separately, each transfer padded with something extra to bribe government officials. It seemed my parents were responsible for supplying goods for the entire extended family. I pored over photo albums looking for more clues. If I caught my parents in a relaxed mood, I might point to a picture and ask, “Who is that?” If the person was alive, they would tell me where they were living. If not, they would murmur and turn the page.

In high school, American history class ended with the Cuban missile crisis and our world history class, having started with ancient civilizations, only got as far as World War II. No one seemed to think it was important to teach me about the Vietnam war, our place in it, or what happened after. I learned to be afraid to ask. The wall my parents erected to repel any curiosity about our past stood fast, too tall for me to climb, unmoving when I pounded my fists on it.

Now, I had blasted through my parents’ resistance to land back in Saigon. But instead of sinking into anonymity, David and I stood out for violating all the local expectations of polite separation. We swept our own floors and hung laundry on the roof. We snuck out to get street food and a few cheap restaurant meals a week, and otherwise bought and cooked our own food. I didn’t want to forfeit trips to local markets to trigger childhood smell memories and to explore, fingering vegetables with unfamiliar skin textures, or to ogle open baskets of giant prawns and squirming eels.

To our neighbors, these lapses in etiquette served as an invitation. Huong, a plump naval housewife across the alley from us, padded over in flip flops to survey my kitchen, the important looking reports on our coffee table, the laptops with their black rats’ tail adapters. She hid nothing in her punchy smile and unapologetically northern accent, loudly peppering conversation with questions about my que huong (ancestral homeland), our salaries (in Vietnam and America, before and after taxes), what our parents did for a living, whether my siblings had married Vietnamese women, and our rent, all the while making cheerful observations about the unfamiliar brands of soy sauce and odd cereal boxes on our shelves. Then, having politely excused herself as I put out dishes for dinner, she efficiently transmitted the new intelligence to all her girlfriends. ‘She’s not here or there (north or south),’ I imagined her saying, ‘The accent is all muddy.’

The exchange was not symmetric and Huong did not apologize for that. She revealed that her husband was a naval officer, but nothing about any family they left in the north. She volunteered his official salary, but not the rental income their neighbors collected from expats. And privacy or embarrassment kept her from inviting us into her house, although she came to greet us on the stoop every time we stepped out or arrived back from errands.

To help penetrate the unsaid and feel more competent at work, David and I registered for private language classes. I was assigned to a stern marm from Hanoi. She sat across a desk from me, impeccably dressed in silk blouses and a bomber jacket, her face framed darkly by a severe bob that Anna Wintour would envy, and led me through brisk oral exercises that always seemed to circle back to comparisons between America and Vietnam. Americans love pop music and movies but they have to borrow real culture from elsewhere; Vietnamese have thousands of years of literature and history. Americans expect everything to be fast; Vietnamese are much more willing to work hard and wait to see the fruits of their labors. I focused on learning new vocabulary but could not stop my irritation from spilling over.

“I see so much in Vietnam that is unique and beautiful. Why do Vietnamese not believe it? Why do Vietnamese have to compare themselves to Americans?” I asked her.

She did not seem startled by my challenge, but she would keep slinging cultural arrows at me, using me for target practice and as a benchmark for her own self-assurance. She redirected me to the short essay I had written for homework and began redlining my awkward grammar.

“Chi (miss),” she said, “when you speak Vietnamese it sounds natural, but not when you write it.”

My family had “wandered” from Saigon to Philadelphia in 1975 when I was seven, hopscotching from a nighttime cargo flight to refugee camps in Guam, Manila, and Arkansas. I learned accent-less English in one summer of intensive tutoring from my father, who had studied in the U.S. in the 1960’s, and my older brothers; I began second grade competent enough that it never occurred to the adults to offer special help to the first Asian kid to enroll at Henry Houston Elementary.

Our home life was almost mute except for transactional conversation. My parents expected us to speak Vietnamese with them, which meant English fluency was useless at home, but unlike my older brothers I had neither enough Vietnamese vocabulary or grammar to say or probe deeply about what actually mattered.

Though bewildered by my new world and my alien status within it, I found it easier to navigate the mysteries outside than the ones in my own house. I had a gift and tropism for muddying my own sense of identity. I grew up a cultural Zelig, using my medium-tone skin and malleable diction to flit between groups of white and black friends, to slip awkwardly but unobtrusively into choirs at the Vietnamese Catholic congregation where we occasionally went or the African American Baptist one near our house.

Now, I sensed familiar accusations from locals, foreigners, sometimes my own relatives, about aspects of my half-status, a fascination and skepticism about how much of my otherness was involuntary versus subterfuge.

A Canadian expat friend often reminded me, “Please move around wherever you’re going to meet me so I can find you. When you stand perfectly still, I can’t tell you apart from the locals. When you move, you look like a member of the People’s Committee.”

I carried my shoulders broadly, walked with long un-ladylike strides, and seemed taller than I actually was. When I was in a hurry and flagged down a motorbike, Manhattan taxi-style on tiptoes with legs spread and a commanding wave of my hand, only more daring drivers with new, larger vehicles came. When I stood still and instead signaled with just a tilt of my head, I could fool anybody, and drivers would be oblivious to my provenance until I couldn’t understand their thick southern accents when asking about the fare and had to ask them to repeat it.

When I wandered into a linen store to look for the embroidered tablecloths my mother asked for, the clerk patiently laid out samples and explained the classic Chinese scenery and symbols on each. Then she sized me up. She checked that no one else was in the store and asked me where I was from.

“I live in America,” I said, and that was enough for her to begin whispering urgently.

She had tried to flee the country, paying smugglers for a boat ride to the Philippines, only to see police boarding the vessel in harbor as she approached it. She was ready to try again. She would bring food and papers, one change of clothes, and money in her shoes, so as not to draw attention with more than one bag. This time the boat would leave downriver, outside town. She thought the trip might take a week, and once in Manilla, she would contact relatives in Australia to sponsor her immigration. She wanted my opinion, wasn’t it a good plan? I froze in the moment, taken aback by her belief that a connection with me would somehow confer luck and safe passage to a better life, and my own unwillingness to scuttle the fantasy that I was her live talisman, because hope is so precious.

I tried not to draw attention to my ‘muddy’ accent. I unconsciously adopted a mild southern drawl. It surfaced when I spoke to shopkeepers and hotel clerks. When I spoke to doctors at the medical school where I worked, my clipped northern accent kicked in instead. If anyone detected the fraud, they were too polite to say. My vocabulary expanded exponentially as the language lessons stretched on, and newly familiar words leapt off store signs and newspaper headlines, but it was easier to read signs than try to catch all the guttural syllables that hawkers squawked at the market. I made my purchases by pointing to what I wanted and signaling numbers with my hands. If the seller gave me more of a vegetable than I needed, I just took it.

Over months of meeting with relatives along the span of the country and the political spectrum, I got better at explaining my work and softening expectations for when my parents might come visit while watching for the subtle clues they dropped about family history or how to navigate Vietnam’s modern reality. In the north, my mother’s relatives held high Party positions and cast a protective shadow over me and David with the implicit understanding that we would do nothing to embarrass them or endanger their standing. Descended from landed mandarins of the old pre-Communist order and thus fallen out of favor, my father’s relatives were conversely just striving to discreetly climb to a sustainable livelihood. They left unsaid hopes that my parents would continue remittances, and that my status might lift theirs. Conveniently (for them and for me), our language lessons didn’t prioritize vocabulary of emotions; I couldn’t burden them with my stress and anxiety.

Sometimes locals decided that the exoticism and status of associating with me was not worth the risk. I was interested in seeing a hospital that was not part of the medical school; someone introduced me to a young surgeon and we met in the courtyard of his hospital for a tour. He was just older than me, smartly dressed, sunglasses dangling from his shirt pocket. I slipped into my anonymous posture as he led me through operating rooms. He pointed to new and old anesthesiology equipment and monitors, explaining the intricacies of resource allocation – how non-urgent patients were selected and scheduled, the hierarchy of influence among staff, the allure of competing for training stints abroad in Singapore or China. I asked him about his caseload, how patients got post-operative care and rehab, and he answered all my questions with an unhurried directness. He told me not to use the term nha thuong for hospital; it was a holdover from pre-revolutionary days that in modern Vietnamese meant an insane asylum. When our tour was done, we crossed the avenue to a café for lemonade and it was my turn to answer his questions about physician pay in America, different types of hospitals, and the length of subspecialty training. As a last thought before we parted, I told him that I was here working for a U.S. organization and that I thought the government was tracking me because of suspicious responses in Hanoi after I sent a less-than-flattering email about Vietnamese health care. He stiffened slightly. We said good-bye and he didn’t answer my calls thereafter.

Yet others were willing to take extreme risks to make and keep connections with me. At the foreign joint venture clinic where I saw patients part-time, I did not even try to be anonymous. The staff were a mix of Australian and American physicians, bilingual Vietnamese nurses, and two young Vietnamese internists. Most patients were new because the clinic was new, but I managed to build a panel of regulars after just a few weeks. They insisted on seeing Bac Si Mai (Doctor Mai) and not a substitute, though they had to wait longer for appointments because I was available only two days a week. Our nurses told me patients of all ages and backgrounds were intrigued by the free-thinking young woman doctor who bothered to explain their illnesses to them, and charmed by my gestures like bending down to tie an elderly patient’s shoelaces at the end of an exam. The fees were hefty, though not exorbitant, for the targeted demographic of independent-minded Saigonese and villagers from surrounding areas drawn by the promise of modern care. Some were peasants and traveled over a hundred miles. They did not seem to mind my awkward Vietnamese, and the nurses translated my more technical instructions. I tried to cram the basics of self-care for diabetes into the first visit for any patient with the disease, uncertain if they would be able to afford another visit. I saw advanced stages of conditions I had only read about. One man in his seventies with severe arthritis and an elevated iron level had true hemochromatosis (iron overload), something I had never seen in medical training in America, and dutifully returned thrice weekly for treatment.

The gynecology residents conscripted to collect data for my research study were all southerners and of an impish sort, also unafraid of associating with me. They knew that what they were observing and recording for me of their professors’ clinical behaviors would not be flattering, and that I was barely qualified to be teaching them research methods I had learned myself just six months before. Yet they assessed our discussions, often about how to critically read medical literature, as a fair exchange for the risks they took on my behalf. Any kind of critical thinking implied irreverence, and southern, post-war, twenty-somethings seized the opportunity to ride in the slipstream of a prestigious American-funded study, to question authority and push gently on boundaries.

I wandered into other forbidden places. My boss, an American anthropologist, brought me down to the Mekong Delta one weekend for fieldwork. We interviewed and camped overnight with a gypsy community of gay, lesbian, and transgender outcasts and runaways, an exercise that was part trust-building and part data collection to better understand the cultural fault lines allowing HIV transmission to rip through the country. I wasn’t officially contributing, but my boss could sneak me into her entourage and not white staff members. I blended in.

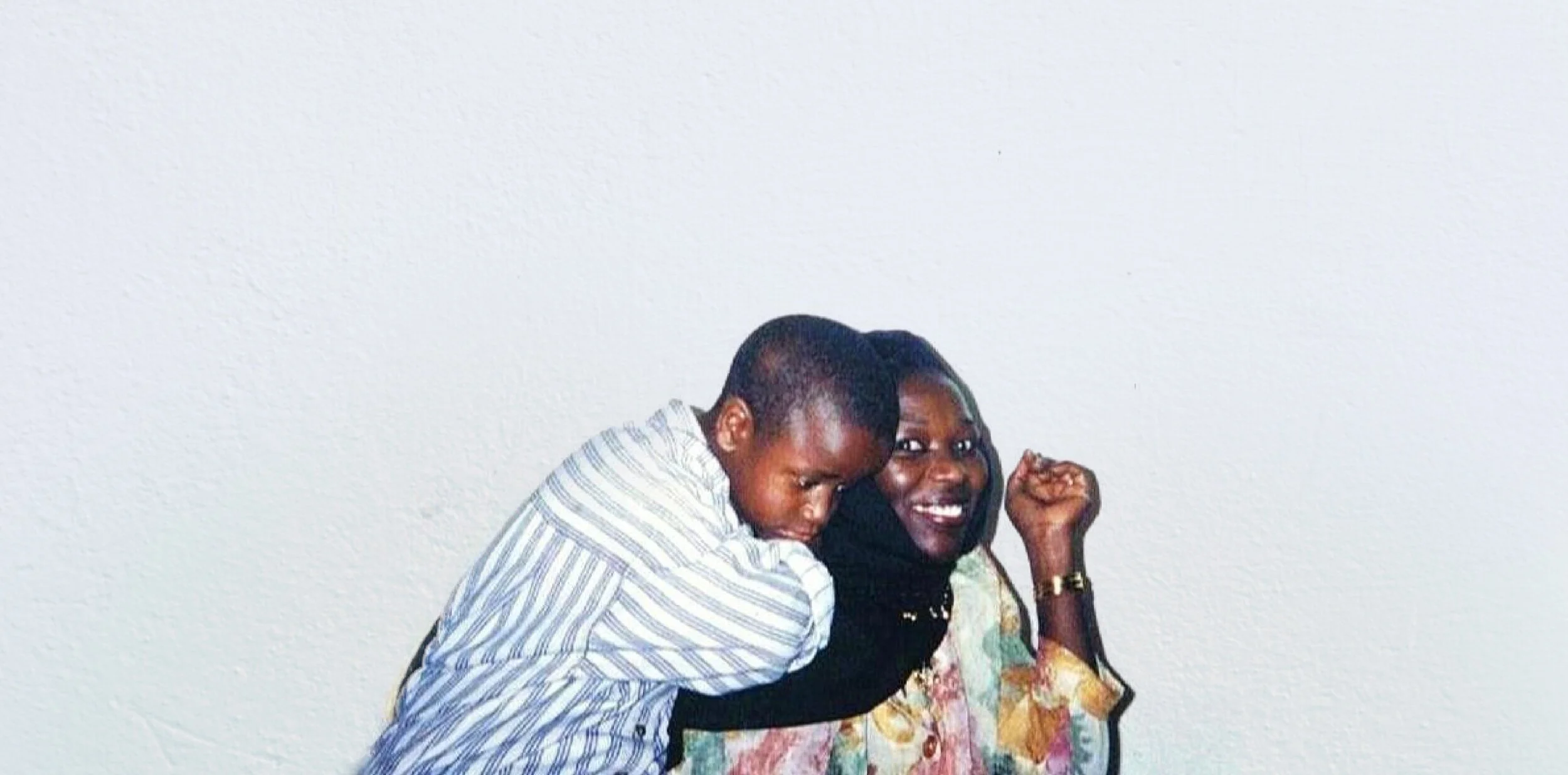

In February, when I recognized signs of my early pregnancy, the radiologist at my clinic insisted on performing a free ultrasound. She showed me the tiny sac and its throbbing blob of life. Inspired by the print-outs she gave me, I went to an upscale clothing shop and had them embroider the fronts of a mommy-sized and a baby-sized T-shirt each with “San xuat tai Vietnam,” and the translation on the backs, “Made in Vietnam.”

In early spring, out of clothes that fit, I passed over tourist shops and instead opted for cheap locally-made tent dresses that were easier than skirts and pants. Now, when I walked with David there was more staring than usual from the people we passed, some cold, some warm, dependent on whether they thought I was cheap or smart to be carrying his child. My condition did not seem to deter any woman, from teenager to middle-aged, who wanted to flirt with him. In the late 1990’s many Vietnamese women assumed white men were gateways to a better life, but David was particularly easy on the eyes and something about his slow smile, open expression, and earnest attempts at speaking Vietnamese made him seem approachable and desirable. The Vietnamese for “Jewish” (do thai) literally means “intelligent and clever.” They had no trouble typing him, and nodded smilingly with approval at him. What was not to like? They discounted the ring on my finger, or didn’t notice it at all. Why wouldn’t they compete with my near-whore status?

Our last few months in Vietnam ushered in my second trimester. Laptop cutting into my belly, I pored over our notes about family stories collected from relatives and our long, journal-like emails to friends and family in the States about the textures of that year, anticipating the aching nostalgia we would soon feel. I closed out my research project with a satisfying if slightly tense presentation of our findings to the very doctors whose diagnostic and prescribing behaviors we had found grossly out of step with national and international standards.

Pregnancies are selfish by necessity. The expanding, parasitic placenta worms into your tissues and recodes reflexes, all to get the new life it needs. I took my time swimming and eating, reworked my walking and sleeping posture as the baby demanded.

The incubation in my belly also forced a new conservation of energy, chipping away at the forbearance it had taken to let others project their fears and desires onto me, the openness and vulnerability required to learn anything meaningful about family or history in that deeply traumatized land, the disciplined self-editing necessary to keep my blunt American voice from smashing the fragile, fraught relationships that branched out in every direction of our lives there.

I had taken and given plenty since coming back to Vietnam, but I had lost track of the effort it took to sustain a fair exchange, or even to do the accounting. Who owes whom how much of what? At the end of June, six months pregnant and instinctively yearning to settle and nest, we made one final round of visits with Saigon relatives, gave Huong the remainder of our household items, and boarded a flight eastward over the Pacific. My parents met their grandson in utero at Newark International, and we slept together on the car ride home to Philadelphia, three generations of ghosts with layered migrations still in flight, but content with our destinations.