Pishi

content advisory: sexual assault, suicide

Ever since I was young, I’ve lost track of time. When I was a child and lived in Iran, whole days and weeks would disappear, along with all the bad things that happened to me during that time. When I was older and studied psychology in America, I learned about dissociation and its roots in trauma.

I was an undocumented immigrant living in New Jersey in the first a few years of my arrival to America. I had moved from New York to the Jersey Shore in hopes of studying at Atlantic Community College, the only college that accepted me without papers. When you are young, alone, and an undocumented immigrant you need to be resourceful. Since the law barred undocumented people from getting a driver’s license, I used to hitchhike to college. Lots of creepy men would try to pick me up, but there were also a few women who would come by at regular times, gesturing at me frantically to get in their cars: “Are you crazy? And in those short shorts?”

I learned to time my travel according to the schedules of these women. I knew them by the colors of their cars and the time they passed my stretch of highway in Mays Landing: White: 7:00am, Dark Blue: 7:30am, Black: 8:05am.

But one day I lost track of time, and when I became aware again it was 8:30am. I had to give a school presentation at nine! I found myself standing by the side of the road, feeling desperate, when an enormous eighteen-wheel truck approached. For some reason I still don’t understand, I flagged it down. The driver was an enormous man wearing a bandanna and reflective glasses. He screeched to a halt fifty yards ahead of me and started to back up. Everything inside of me was screaming not to get in, but a reckless part of me took over. I don’t care, the voice said, you know damn well I’m out of options.

I’d never climbed the ladder of a truck before, and it was difficult to get into the cab. Once inside, I immediately understood my mistake. The man didn’t look me in the face at all he just ran his eyes up and down my bare legs and didn’t reply when I told him the address of my school. We pulled onto the highway in silence, and something about the energy in the cab started to feel familiar. At some point, he pulled out a pack of cigarettes, lit one, and offered me the same. I nodded to say sure, and he lay the pack on my thigh, letting his fingers brush my flesh.

As the man’s hand moved on my leg, a rage rose in my throat. I looked out the window of the passenger-side door and saw that we were more than ten feet off the ground. We were going sixty mph. I’m dead if I jump. So I turned to him and said, “This has happened to me before, you know, when I was very little.”

The man said nothing, but his hand stopped moving.

“It won’t be the first time,” I said. “I know how this goes.”

Suddenly the man’s mouth opened.

“How little?” he asked.

“Before I could even talk very well,” I said.

He tilted his head towards me, pulled his glasses down just enough, and his eyes met mine for the first time. I moved my body toward him so I could see his eyes. Then he turned to face the road, slowed the truck down, and veered onto the shoulder of the highway.

“Get the fuck out of my truck before I change my mind,” he said.

The next thing I knew, I was at home, talking to my roommate.

“How did you get out of that truck?” she was asking me.

“I told him I’d been raped before as a child,” I said. “Something about saying that made him let me go.”

“Who were you raped by?” Ivy asked.

“Since I left Iran, I can hardly remember anything,” I said. “I hardly remember my own mother. It’s just lots of flashbacks. The thing is, I can’t for the life of me remember how I got into that truck in the first place, or how I got home after.”

“Well, you were just telling me you were hitchhiking,” she said, frowning. “You talked your way out of getting raped and walked home.”

“I did?” I responded.

How could she know more about my day than I did? At that moment, I felt the weight of all the time that had disappeared from me. It was as though my eyes were closed, but I was touching some large object, learning it by feel. There is so much I don’t know, and once again I felt the darkness come and fold me into it. Maybe the doctor in Iran was right.

Maybe there is a reason I forget things. I felt a tired and drowning feeling start to spread across my chest.

The next thing I knew was that I woke up in my bed. It was just after dusk, and the snow was piling up outside. The seasons have changed, but I haven’t. I’m still undocumented, in danger, and failing out of school for being absent too often. Once again, I hadn’t gone to school that day, because I didn’t have a ride, and ever since the incident with the trucker, I couldn’t bring myself to hitchhike. Ivy was with her new boyfriend. The house was cold and empty.

I remember my thoughts starting off in a kind tone of voice. This time, do it so it doesn’t hurt, they said. No bleach, no drowning, no jumping out a window. Just a long sleep we don’t wake from.

I left Iran because I wanted to be free. Maybe this is how I’m supposed to get free. No more finding myself in the middle of a conversation with someone I don’t know, no more finding myself in places I don’t recognize, no more coming to my senses as I’m crossing a highway and nearly getting hit by a car. No more surprises.

I knew that I needed to act fast, before other thoughts took over. I got dressed and walked through the snow to the nearest pharmacy a mile away. I hadn’t done any research, so I just gathered all the medications that seemed soothing — NyQuil, aspirin, Tylenol — and brought them up to the check-out counter. The cashier looked concerned and before she could speak I told her, “My whole house is sick.” She rang me up reluctantly.

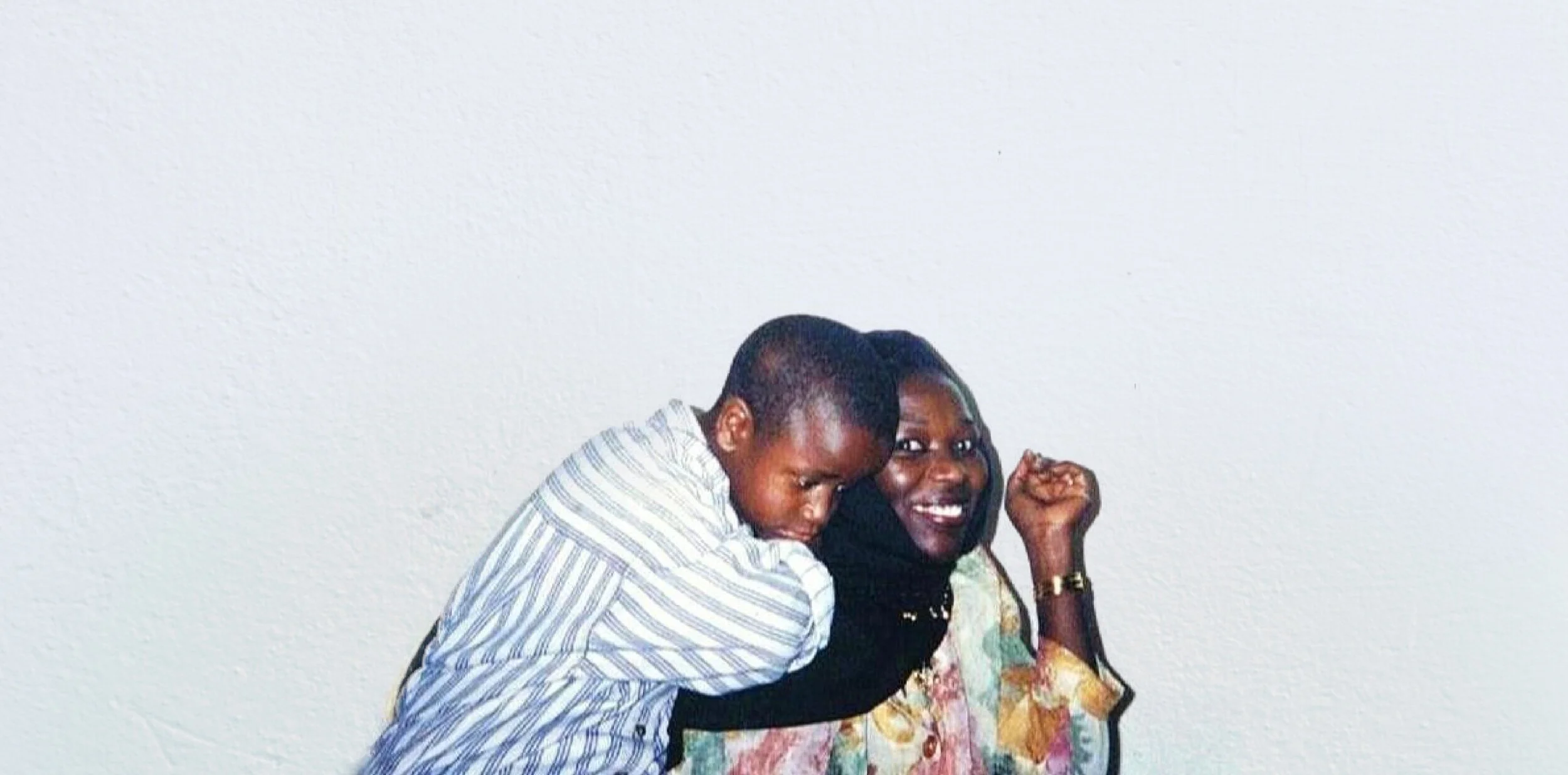

Back outside, I felt a strange energy coursing through my body. I have a purpose. I didn’t feel sad at all. I went through a mental list of all the people who would be upset, but their grief didn’t register. Only when I thought about my brother and how I’d promised to get him out of Iran one day did I start to cry. I wiped off my tears and walked faster. Maybe it’s better for him to stay in Iran anyway. He’s a man. He’ll find his way.

Sounds intensified as my focus sharpened. I could hear the crunch of snow beneath my boots and conversations in the distance. The cold wind on my face took my breath away. It felt good to feel before I die. I was absorbed in these last sensations. Then I heard a squeaking sound, like the cry of a mouse, coming from a nearby parking lot. I followed the sound to the gap behind a parked car and a snow bank where I caught sight of a little fluffy ball bounding toward me with great purpose. The ball aimed itself at my boot, collided with it, and then collapsed at my feet. I picked it up: it was a black-and-white kitten, shivering, barely alive but still breathing audibly. I put the kitten inside my coat and could hear its little heart beating against mine.

“Pishi,” I said, using the Persian word for kitten. Pishi gave a little squeak from inside my coat which I took as approval for her new name.

I ran home with the kitten in my coat, leaving my bags of medication behind me in the snow. I gave her a warm bath and fed her. Then I fell asleep with her in my arms.

In the morning, Pishi woke me. She was chasing her little tail and jumping up and down on my bed. The sun was shining brightly that morning. I started to cry. The dark voices inside me were gone.

I saved Pishi’s life the night before. In the morning, I realized she had also saved mine.