More Than Skin Deep

Brown or White? How Health Conditions Can Affect Cultural Identity

Growing up as a Mexican immigrant in the mid-80s in a predominantly white suburb of Los Angeles, California – at the age of seven – my long, braided pig tails, second-hand clothing, lack of English skills, and brown skin fit in as much as my father’s early 70s hooptie. My classmates were tall, white, blonde, and middle class. While I didn’t have my mother’s milky white complexion, I embraced my brownness as I shared it with my father who was nicknamed El Prieto – the dark one – by my great grandfather who had fair skin and blue eyes. He would tell my father that he loved him most among all his grandkids because he was unique: dark like a Liver Chestnut/Black horse, hence my strong desire to look just like my daddy.

Throughout my K-12 education, I was never fully accepted by my classmates, especially when the students of color at all my schools could be counted – on one hand. While my peers never embraced my brownness, in high school, I imagined they were secretly envious of my natural tan as they attempted to replicate it at tanning salons, especially during prom season. “Wishful thinking!” I thought. Likewise, I took every opportunity to sunbathe – to become even darker. I loved the fact that my skin color was a deep golden brown just like a churro.

Five years ago, when I was diagnosed with Vitiligo (vit-uh-lie-go) – a non-contagious skin disorder that causes loss of pigmentation resulting in random white patches – I was faced with the sobering reality that I may one day lose my brownness. Vitiligo, which affects 2% of the world population, is incurable and unpredictable as there is no telling how much it will advance. For some people, it takes a lifetime to fully “transition” – the term used to define those who turn completely white. Others, however, transition in just a few years.

My vitiligo started as a tiny dot on my right thumb until last year when it started to spread more on my hands, underarms and on my torso. Although there are a few treatments available, what I've tried hasn't worked (topical and costly creams that are not covered by health insurance). Drastic treatments include skin grafting, PUVA light treatment or bleaching of the skin – none which I plan on doing. To camouflage the spots on certain public outings, I use costly, waterproof professional make up or self-tanning lotion – not the best as my hands sometimes resemble those of an Oompa Loompa. Other times when I'm brave, mainly around my hubby and immediate family, I don't use anything at all to hide the spots which is both liberating and frightening as I don't like to be judged or stared at.

While the disease doesn't cause physical pain, the emotional and psychological effects are agonizing, especially when people make hurtful comments. Three years ago, a “friend” asked, “Oh, my God! What’s wrong with your hands? You don’t have that **it do you?” It was easier to lie and say the white spots were scars rather than admitting I had vitiligo. The possibility of not being accepted due to my skin condition was troublesome perhaps because it was reminiscent of my childhood experience. I didn’t think I would have to go through that again – certainly not as an adult.

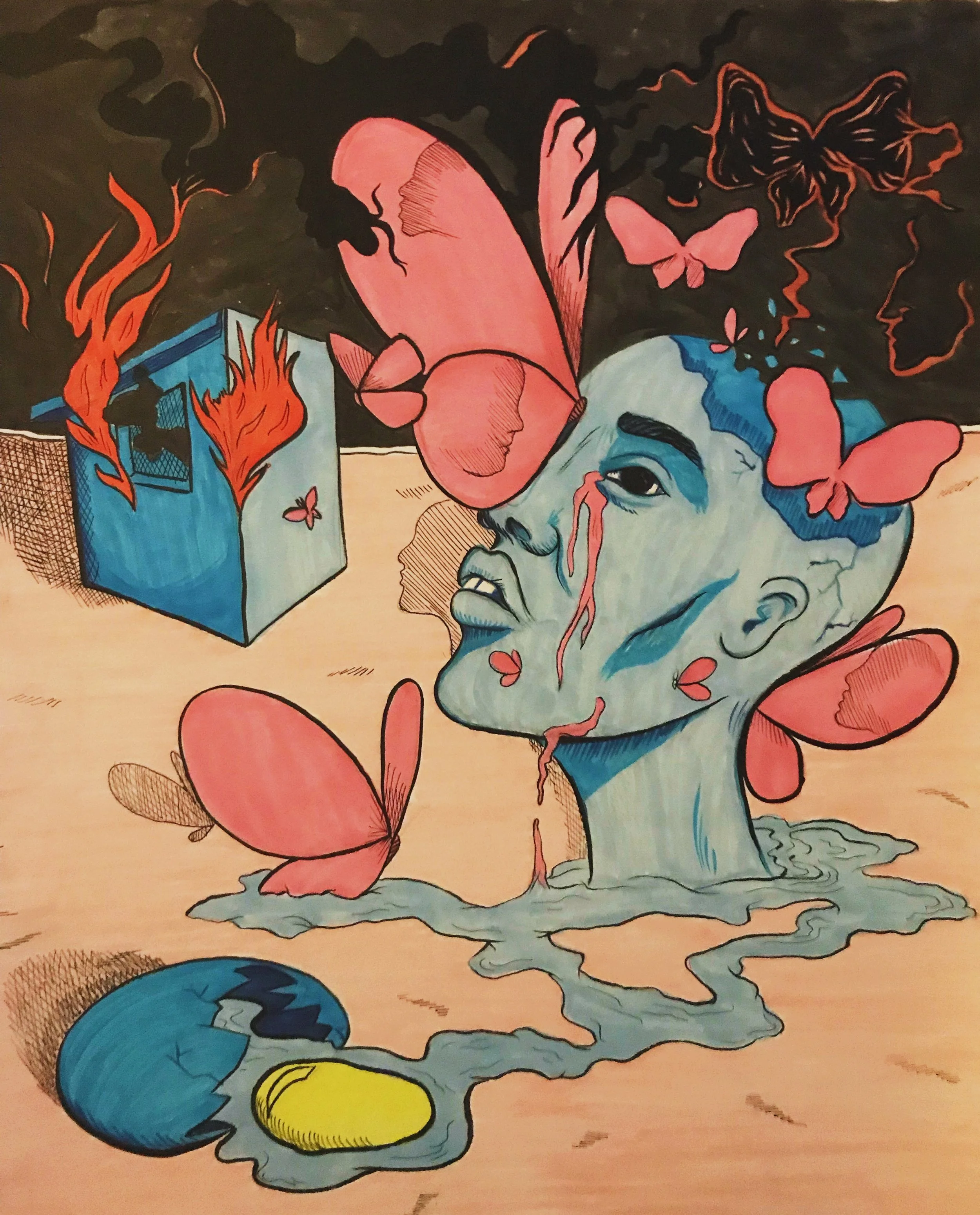

the author with her father

Despite the relatively slow progression of the condition, the thought of my entire body turning completely white is unnerving. While I did experience racism growing up in suburbia, I never disliked the color of my skin nor did I have trouble balancing my cultural identity. On the contrary, my darkness has been a badge of honor. As a daughter of peasant farmers, I have always associated my brown skin with generations of hard, manual, honorable labor. Farming has always been part of my family history both in Mexico and the U.S. The men and women in my family developed their color through long hours doing what is essential for the survival of society – feed mankind. I’m proud of the many generations who have toiled endlessly in inclement weather and dangerous conditions, often earning less-than-minimum wage while performing their tasks with expeditious accuracy to meet production deadlines.

Some of my fondest memories as a child in Mexico are of my grandmother and mother cooking gorditas, tacos or home-made tortillas for my grandfather, father and brothers who started their workday at dawn. It was a tradition for the women to walk to the fields to have lunch with the men. We would sit on rocks strategically placed in a circle under a mesquite tree as we devoured the freshly cooked meals while basking in the scent of wet, recently plowed soil. The horses used for plowing would also break as they foraged in the fields. While our meals reflected a poor lifestyle by societal standards, we were wealthy in family bonding time that spanned three generations of beautiful, brown people – people of the earth and sun. It was a simple, carefree daily routine; it was perfection.

Since I didn’t grow up in urban areas like many Mexican immigrants in California, I have often been called a coconut (brown on the outside, white on the inside) which I take as a challenge to prove my heritage. As a married, childless (by choice), vegan woman with an advanced degree, many have questioned my Mexican roots. “What kind of Mexican are you?” is a question I have been asked frequently when I don’t fit the traditional norms of what a Mexican woman should be. While not being accepted in suburbia made sense growing up, not fitting in with my own people is baffling. Consequently, I have sometimes wondered if I belong anywhere as I have been labeled a “Unicorn” because Mexicans like me “don’t exist”, “too American” and “too Mexican” both in the U.S. and Motherland when I visit.

I imagine that as my vitiligo continues to increase, so will the types of questions and tags with which people will associate me. I may not be able to alter my vitiligo or the limited views some have of me. However, I can change how I respond to the categorization as I know that I am more than a color. Above all I am a woman with a rich life history that connects me to others who are different. Vitiligo has taught me to be more accepting and less judgmental. By focusing on the commonalities rather than differences, I’m creating peace of mind which is empowering and humbling.

I can’t predict how white I will become as my vitiligo advances or how I will react to continue defending my cultural identity if my brownness continues to be stripped away – one spot at a time. Until then I’m embracing my rich, diverse heritage: 48% Native American, 38% European, 10% East Asian and 4% West African. I am the product of many cultures weaved like a beautiful silk tapestry. Vitiligo may alter my complexion, it may defy me, but it won’t define me or my cultural identify as it is more than skin deep. It’s my roots, family history, and soul. Nothing or no one will change that. Ever.